14/12/25

Is there an AI bubble and will it pop next year?

Experts discuss what investors need to know for 2026 at the annual FT Money roundtable

This article is republished from The Financial Times

Experts discuss what investors need to know for 2026 at the annual FT Money roundtable

Anyone with an upturned glass to the door of the conference room we met in last week could have been forgiven for thinking we were rehearsing a scene from Macbeth.

“Bubble.” “Bubble.” “No.” “Not yet.” “No trouble.”

In fact, I had asked the panel of five experts gathered for FT Money’s annual investment roundtable the Big One: whether the valuations of AI companies are irrationally overinflated — and what were the chances it would all go pop next year?

Before a twinkling Christmas tree, with the dome of St Paul’s framed in the picture window behind it, we discussed what retail investors should look out for in 2026.

Joining the discussion were FT columnists Stuart Kirk and Katie Martin; Simon Edelsten, a fund manager at Goshawk Asset Management; Niamh Brodie-Machura, chief investment officer of the equities team at Fidelity International; and Iain Stealey, chief investment officer of the global fixed income, currency and commodities team at JPMorgan Asset Management.

Hands up, who thinks AI is a bubble?

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the room was divided along professional lines — with the two journalists happy to use the B-word, and those responsible for running clients’ money more optimistic about the state of the market.

“There are two things to know about bubbles, historically,” said Edelsten. “The first one is that bubbles are notorious because everyone is a buyer at the top.” The current level of concern and dissent was absent, he argued, from the tulip mania, for example, or the crash of 1929.

“But the more important, less cynical point, is the valuation point,” he said. “I think it’s very different from 2000, when basically everything was nuts: there was no valuation basis for a huge number of very large companies, across Wall Street and Europe.” That is not true of the best AI stocks today.

Nvidia has a price-to-forward-earnings ratio of about 25; Amazon and Microsoft are in the high 20s — not cheap, but nowhere near as wild as some telecoms companies at the height of the dotcom boom.

“These are extremely strong companies from a fundamental perspective,” said Brodie-Machura. “The demand is across all parts of the supply chain, and it is in excess of what can be supplied at the moment, which means you have volume growth and pricing power at the same time.”

Stealey said that, from a bondholder’s point of view, he was “pretty comfortable” with the state of the market — though he made a distinction between some of the hyperscalers with huge cash piles and companies such as Oracle, which have much higher debt levels.

“And I know we had this indigestion over the past six weeks or so, where we’ve had big issuance from Meta [and Alphabet], and it did cause spreads to widen a little bit — but, to us, that’s a buying opportunity,” he said.

“These are very highly rated [bonds], and there is liquidity sloshing around in the system, and people are desperate for yield at the moment.”

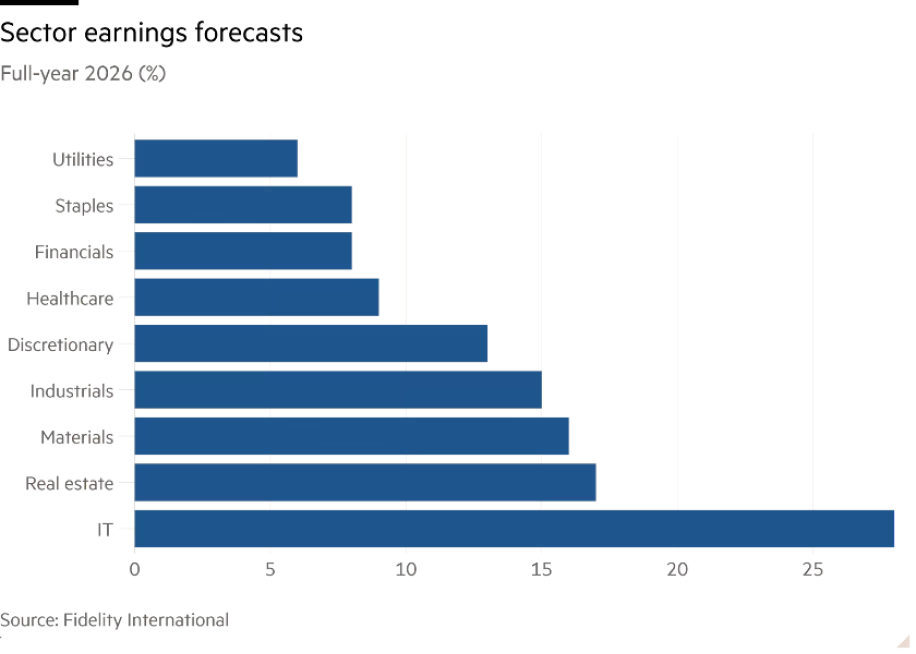

Next year, Fidelity analysts predict 28 per cent growth in tech sector earnings and for growth to broaden out.

Nobody wants to be the naive investor that got in at the top, said Brodie-Machura. “But then nobody wants to be the cynic sitting on the side . . . at a point in time where many participants think this may be the biggest inflection point for human productivity since the industrial revolution.”

“The stakes are really high,” she added. “If it doesn’t work, the risk of capital loss is real. If it does work, this [growth] can absolutely continue.”

But it’s not an argument that landed with Kirk — who recently liquidated his equity fund holdings, and is now 100 per cent in cash.

“Having worked through four or five bubbles, where people told me ‘it’s different this time’, it never is,” he said. “So I discount the upside for AI: it’s just another ‘this time it’s different’ argument.”

Martin said she didn't doubt AI was a potentially transformative technology, but there was clearly “a very thick layer of froth” that needs to come off the market — and some of that would dissipate in 2026.

“Look, I believe that what’s happening with Nvidia is real. I don’t think this is a Pets.com phenomenon,” she said, referring to a poster child of dotcom-era hype. “But you look at some of the things going on in markets and you have to think: if this isn’t bubbly behaviour, then what is it?”

She cited the moment in October when Nvidia chief executive Jensen Huang dined at a fried chicken restaurant in Seoul, causing the share price of one of South Korea’s largest fried-chicken chains to jump 20 per cent (though not the one Huang actually visited, which is privately owned).

Even the share price of a local chicken supplier jumped 30 per cent.

“And you look at this weird, circular-financing, cross-shareholding thing that’s going on at the top of the market, and you think: what is this if it’s not behaviour that tells you there’s excess here?” Martin said. “And I don’t have another word for it other than ‘bubble’.”

What could go wrong next year?

While the room was divided on the bubble question, there was broad agreement that inflation was a major risk for 2026.

Stealey said he still believed the most likely outcome for next year was that inflation in major western economies would stay roughly where it is or trend downwards, allowing central banks to ease rates, which would benefit all financial markets. But interest rate expectations have changed significantly over the course of this year.

“The big risk now is that we see a little bit of what is happening in Australia occur globally,” said Stealey. The Reserve Bank only started its rate-cutting cycle back in February. But with inflation rebounding, governor Michele Bullock has more or less ruled out any more cuts, and warned that hikes may be needed in 2026.

If borrowing becomes more expensive in the US, and this triggers a market sell-off, AI could follow the US housing bubble of the early 2000s, the dotcom bubble of the late 1990s and Japanese asset price bubble of the late 1980s, which all popped when central bankers started raising rates.

While this risk may feel remote, given that the Fed chose to cut rates this week to their lowest level in three years, Edelsten believes there is already more inflation in the system than is being modelled: “I get the feeling that the cost of living is going up much faster than the figures say.”

“Inflation has been tracking a lot higher and is becoming a political issue in America — I was surprised by how little it was mentioned in our UK Budget, because it’s high here too. And this is all against a background where the oil price is weak,” he said.

The ability — and political will — for many western economies to deal with rising prices has become a concern, with the US, UK and Japan all criticised for showing signs of fiscal dominance this year, where monetary policy is determined by budgetary concerns.

At the same time, Kevin Hassett has emerged in recent weeks as the frontrunner to become the next Fed chair in May.

If appointed, many expect him to be obedient to President Trump. Joseph Wang of Monetary Macro even described Hassett as “the most political choice that you can get next to appointing Don Junior”.

“If [Fed] independence gets called into question, right around the time of the midterms, then that might cause a bit of an upset in all financial markets,” said Stealey. But he questioned how likely this would be, pointing to the fact that, even with Hassett the favourite in the betting markets, the 10-year US Treasury yield is still around 4.1 per cent. “At the moment, I think the market is still of the mindset that this is going to be a reasonably independent Federal Reserve,” he said.

If there is a problem with inflation next year, what would be the first signs that something was wrong? “If you started to see a re-acceleration in services [inflation], that would be a concern,” said Stealey. “How would that happen? It would be wages.”

At the moment, concerns about the US labour market are that it’s slowing. “But if you started to see a little more stability and wages start to pick up — and you combine that with the fiscal support that is coming from the One Big Beautiful Bill Act — that’s the concern,” he said.

Investors should have their eyes trained on the second quarter of 2026, since this is when US consumers could be in line for an income tax refund season, thanks to the OBBBA, which could boost demand and put yet more inflationary pressure into the system.

There are other risks that could take a pin to the AI balloon. One is that, for all the technology’s razzle-dazzle, investors will demand to see more evidence of its useful application in commercial settings.

“The spend is definitely happening, the capital deployed is going up,” said Brodie-Machura. “Now we’re looking for the ROI to come through . . . If it falters, or there are risks that it falters, or if the lead players change, [expect] a lot of volatility in the stock market.”

The other big risk, she said, is competition from Chinese AI. In January, DeepSeek stunned Silicon Valley rivals with the release of an AI model that worked at a fraction of the cost of those produced in the US, prompting a major tech sell-off. Another breakthrough like that next year could seriously undermine US stock valuations.

There are also more general risks to markets posed by the possible unwinding of the yen carry trade, due to economic conditions in Japan, and then there are the black swan risks — which the panel thought could come from non-bank lending or crypto or some other overlooked or poorly understood corner of the financial markets.

“It’s usually a product we’ve never heard of before that blows up,” said Kirk. “And it usually has something to do with debt.”

What defensive strategies can investors take?

The room was divided on how investors can protect themselves from a downturn next year, should one occur.

The first thing, said Martin, is that the sheer size of the US tech companies and the concentration in US and global markets, means that were the AI bubble to pop “the blast radius would be enormous”.

But the secondary problem, she said, is how asset managers have told her that their hedging strategies involve moving away from AI stocks into Asian tech, energy infrastructure or copper, which is required for the data centre build-out.

“And I’m like: ‘am I going mad here? This is the same thing!’” Martin said. “You’re hedging out into a different part of the same value chain of the same thing.”

“And so I worry about dominoes,” she added. “And I worry about how deep the damage could be.”

Reasons to be cheerful in 2026?

“The thing that people sometimes forget is how many bad things are going on right now that if they were solved would cause a bit of a rally,” said Stuart Kirk.

He singled out the war in Ukraine and pointed to eastern European bourses where companies were “underpriced relative to something good happening. And maybe 2026 will be the year where that gets fixed somehow.”

Katie Martin agreed that the Ukraine reconstruction trade was interesting. “If I was running a listed cement manufacturer somewhere in Poland, I’d be feeling pretty good about the next five years,” she said. “I’d rather own that than a German defence company on 70-times,” Kirk added.

Niamh Brodie-Machura singled out Chinese tech. She described a chart on the performance gap between the best US AI model and the best Chinese AI model, with independent testing. “And the difference is spend.”

Simon Edelsten picked out China in general. “For British savers looking at their overseas allocation, you’d want to feel that you’ve got a reasonable amount of your savings in China if you’ve got a long-term view . . . it should be a natural part of people’s portfolios and often it sort of drops off the end.”

But both Edelsten and Brodie-Machura were keen to point out that diversification strategies have worked in 2025, citing big gains made in the FTSE 100, European defence and Japan.

“In the past year, you would have made as much money — in sterling — investing in the UK, because the banks have gone up, as you would have made investing in the S&P 500,” said Edelsten.

“You would have made as much money investing in Japan, despite the yen going down, because the market recovered a lot — and none of that was AI.”

For those looking for diversification, there was much discussion about the excitement in so-called quality stocks, which offer a high return on equity, stable earnings growth and low debt levels.

Typically, the quality stocks that people concentrate on are consumer staples, such as Procter & Gamble or Nestlé — but they need to be cheap, said Edelsten. That’s crucial.

“I’m afraid a lot of people have said: ‘oh, for cautious investors, just come and buy quality’ and [they] miss out the ‘cheap’ bit.”

Unfortunately, he added, a lot of these stocks became very expensive during the pandemic, because they were considered safe. “So everyone piled into them, but they don’t grow very fast.”

Edelsten said he was more interested in healthcare stocks. He mentioned United Healthcare — whose former chief executive was shot in Manhattan a year ago — and Johnson & Johnson.

The company has had its problems, he said, but has a good pharmaceutical division and is well placed to develop automation inside healthcare, which could boost productivity.

At 18 times earnings, he said, it’s not very cheap, but it shows that not everything in the US is expensive.

“The American equity market is massive. And although it’s dominated by a small number of companies on some really fancy ratings, as soon as you go down [the list], if you do work, you’ll find plenty of stocks that you’ll think are reasonable.”

But playing defensive is not easy, he added.

“This is one of the reasons that tech investing has carried on. When you look at the alternatives . . . they have had an awful lot of bombs going off. And so switch out of a tech stock, where you hope to make a lot of money, into something where you don’t expect to make an awful lot of money, and then it has a slight wobble on its profits and you’re 20 per cent down and you think, ‘why did I bother to do that, then?’”

Kirk said he thought government bonds were interesting again.

“Whereas maybe nine, 12 months ago, we all thought that no one’s ever buying govvies ever again, that all governments are bust and the returns are awful, but I think if there’s a sell-off next year, government bonds are going up.”

Both Stealey and Brodie-Machura liked the idea of some alternative assets, such as gold. But Martin disagreed, at the risk of sounding like the ghost at the feast.

“Weirdly,” she said, “I’d point to gold as one of my pieces of evidence that markets are bubbly.”

She said the Royal Mint had told her it had introduced a queueing system to its website, because it was becoming so overloaded with people wanting to buy gold “while they’re sitting in front of the telly watching Strictly on a Saturday night”.

“Now,” she added, “these are not people who are sitting around looking at central bank reserve accumulation and thinking about fiat currency debasement or global debt sustainability. They’re hopping on a momentum-driven bubble.”

Are UK stocks at a turning point?

Including dividends, the FTSE 100 is up 22.8 per cent year on year to December 1, outpacing the US S&P 500 by a wide margin.

So is this a turning point for the benchmark, often considered a laggard on the global stage?

“Our team thinks ‘yes’,” said Niamh Brodie-Machura, pointing to an impressive performance this year and the fact that, relatively speaking, the stocks are still cheap.

“There is real value here . . . the free cash flow yield is really good and the dividend yield is really good.”

Stuart Kirk said he was interested in UK small-caps. “They are cheapish . . . And you go down to those levels, and the return on invested capital is sort of insane. You’ve got management teams who are genuinely equity friendly.”

“The catastrophism about the UK is weird apart from everything else,” said Katie Martin.

The fact is, stocks here have done very well, and gilt yields have remained in check.

“Can we get double-digit returns out of the UK next year as well as this year? It’s a punchy bet, but it’s not impossible. It depends on what the dollar does.”

But, she added, the idea — perpetuated by some other newspapers — that Britain is in the grip of some kind of a terrible financial crisis is absurd.

“No,” she said. “We are not about to [be bailed out by] the IMF.”

“If we can achieve nothing else through this little crystal ball gazing session today, if it’s to get people to just stop whingeing about nothing in relation to the UK, then that would be a major achievement.”

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2025 © 2025 The Financial Times Ltd.

All rights reserved.