2/9/25

How to invest in a stock market bubble

The three lessons I learnt as a professional money manager

Sell in May and go away.

Not this year!

Rather than disappearing off to fry on a beach somewhere, investors who stayed put have enjoyed a divine summer in equity markets.

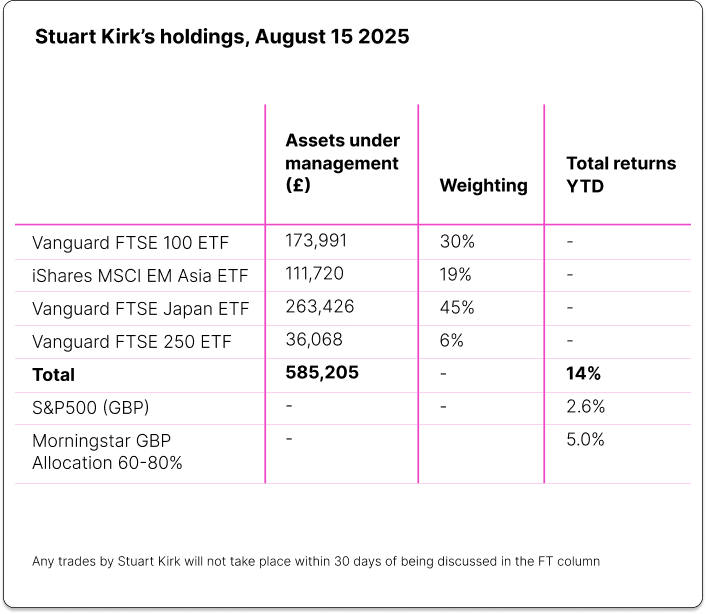

My pension has grown by a cool hundred grand and not a tourist to be seen.

At this rate my portfolio will pass £600,000 by the time I finish typing this sentence. Just four months ago it was £487,000.

That’s an annualised growth rate approaching 90 per cent.

Yes - the decimal point is in the right place.

Man, do I pity everyone who is short. Loads of professional investors have come out all year advising a high allocation to cash.

Some placed bets that stocks will decline. I won’t name them - that’s cruel - but they’re not talking much these days.

I have been there and it sucks. Grumbling about how mad everyone is while hating yourself for missing out. Forwarding charts that show how divorced prices are from fundamentals. Longing to join the party but certain it will end the moment you walk through the door.

It’s even worse for institutional money managers. Those underweight equities or long defensive stocks are miles behind the benchmark.

Bosses have stopped looking them in the eye. So have their PAs. Just hearing the word Nvidia causes arrhythmia.

Of course, none of their bullish colleagues - at lunch again or perusing boats online as they ponder their year-end bonuses - will admit we are in a bubble.

But I am with the doom-mongers all the way - despite being up to my neck in equities.

Looks like a bubble.

Smells like a bubble.

Is a bubble.

US shares in particular are large, round, and shiny with a window reflected on the surface. But equities everywhere are flying because American ones are. And they will pop when the latter do. So it’s a global bubble whether you or I like it or not, even if the Nikkei or Footsie, say, are not expensive.

I won’t list the myriad indicators akin to 1999 or 2007 - from a tsunami in margin borrowing in US broker accounts and insane multiples of revenues to confidence surveys and put-call ratios.

Much has been written in the FT on these already.

Even if you don’t agree now - the way prices are rising you soon may. Hence in this column I wish to pass on what I learned having managed funds professionally during the two biggest bubbles in the past three decades (I missed Japan’s by five years).

First, periods of nutty exuberance last much longer than you expect. Equity markets started to feel hot to the touch a few years after I began as a portfolio manager in 1995. But the dotcom boom saw out the decade. And the rest of the market lasted another three years after that.

It is impossible to know ex-ante how far we are into this bubble.

However, to me it doesn’t feel near the end.

Sure, meme stocks are soaring and AI influencers are launching billion dollar hedge funds. To be 1999 again, the IPO market needs to ignite, with my gardener telling me how much he’s making every day.

The second lesson I learned about bubbles is that prices rise further than your wildest dreams.

As I mentioned above, the Nasdaq index doubled within three years of me donning a suit for the first time. Then it rose another 50 per cent in 12 months. Valuations were loopy. I didn’t know anyone not trading shares.

Surely the end - many of us thought. Hell no. Between the summer of 1999 and the peak in March 2000 the Nasdaq doubled again! Everyone who had gone underweight in those final months because prices made no sense lost their relative shirts. And their minds.

Many lost their jobs, too.

Even two years before the peak I sat near a (now famous) UK fund manager who simply refused to buy dotcom stocks on valuation grounds. Poor bloke “didn’t get it” was the prevailing view. Out he went.

I’ve said in previous column that crazy markets over my career tended to last about 10 years before something blew up - often towards the end of a decade.

Why? Because it takes that long for investors to forget the past, recover their animal spirits, and buy stuff again they shouldn’t.

Irrespective of whether you set your watch by the 2020 or 2022 corrections, therefore, we may have a way to go - with the usual caveat that past performance is no guarantee blah blah.

Which brings me to a final piece of advice when investing in a bubble.

And that is to ignore everything I’ve told you about passive versus active funds.

%201%402x.avif)

To be sure, there is still no reason to pay exorbitant fees in the hope that a portfolio manager can pick the right stocks.

Most are sensible and — like my ex-colleague - can’t in good consciousness buy shares at nutty valuations.

This means they increasingly underperform near the top, as they are again now. But nor should you give the ultra-bullish Cathie Woods of this world your money.

It’s cheaper and easier just to do what they do and own the few stocks that have contributed most to inflating the market. Buy even more on the dips.

That’s because winners become ever more concentrated. So they are easy to pick - even if it feels wrong to own them.

Then, as soon as the bubble bursts - don’t worry, you’ll know - switch to passive funds again.

Bonds are best. Equities are fine, too, but make sure they have the word VALUE in the name.

Then you really can disappear for the summer.

Perhaps many summers.

While everyone back at home freezes their bums off.

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2025

© 2025 The Financial Times Ltd. All rights reserved.