11/11/25

How Warren Buffett Built His Fortune - and 10 Lessons to Build Yours

How Warren Buffett Built His Fortune — and 10 Lessons to Build Yours

Every morning in Omaha, Nebraska, a man worth more than $160 billion drives himself to McDonald’s.

If the stock market is up, he orders the bacon-egg-and-cheese biscuit. If it’s down, he downgrades to sausage.

He pays in exact change, usually less than four dollars.

To most people, the ritual seems absurd: a billionaire buying breakfast like a pensioner.

But to Warren Buffett, chairman of Berkshire Hathaway, it’s not thrift so much as philosophy — a small daily act of order in a chaotic world.

Buffett, now ninety-five, is known as the Oracle of Omaha.

Yet his genius has never been prophecy. It’s patience.

He built one of the most valuable companies in history by doing the simplest things with near-religious consistency.

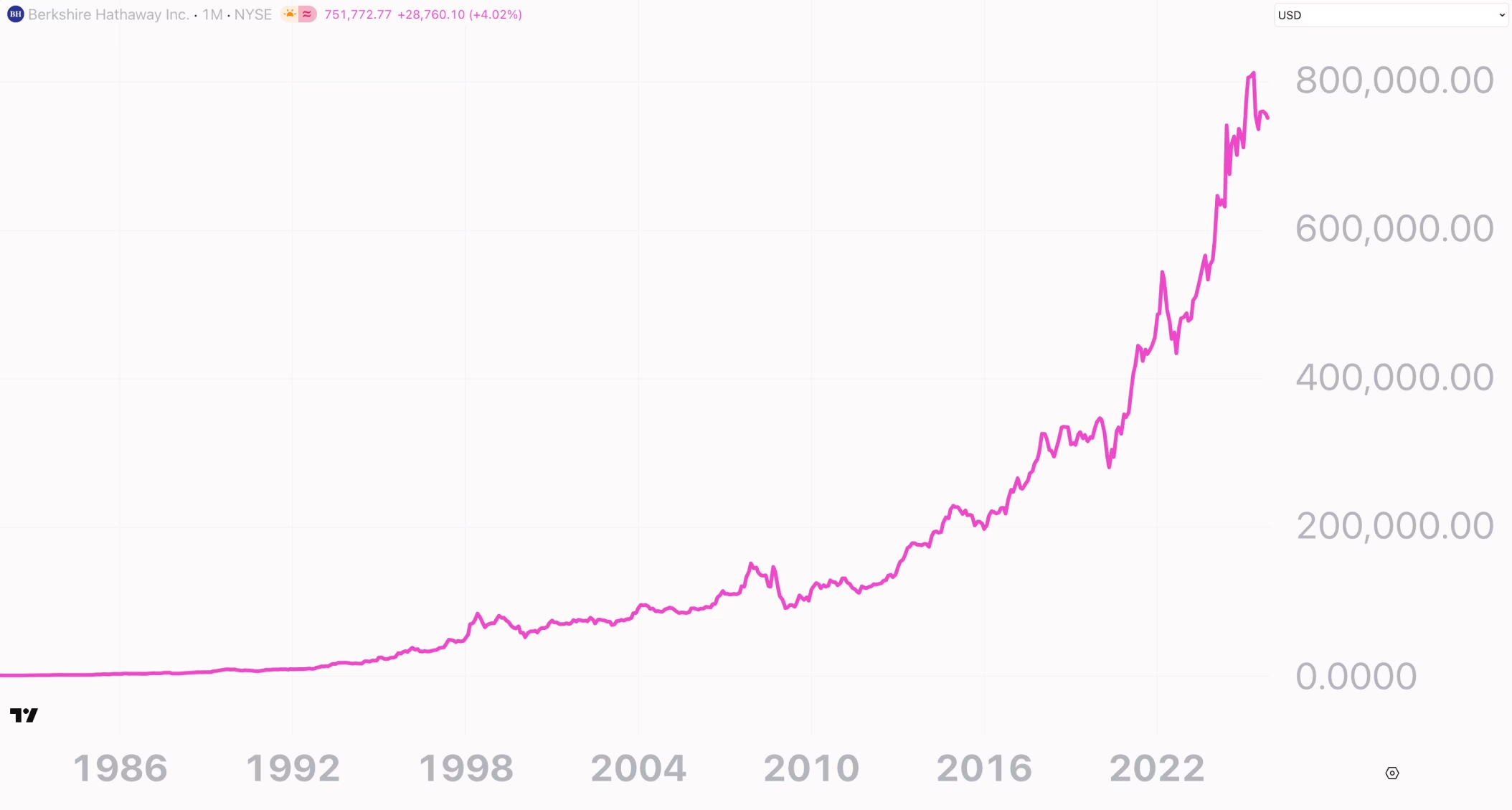

Here’s the number that captures his magic: about 95 percent of Buffett’s net worth — roughly $150 billion — was earned after his 65th birthday. ¹

That isn’t luck.

It’s the quiet miracle of compound interest, the process of earning returns on your previous returns.

In the early years, growth feels invisible; then suddenly the curve bends upward and time becomes an ally.

Buffett likes to say, “My wealth has come from a combination of living in America, some lucky genes, and compound interest.” ²

To Buffett, it’s not a joke. It’s a worldview: wealth is less about brilliance than endurance.

As he gradually steps back from Berkshire Hathaway, which owns or holds major stakes in companies like Coca-Cola, Apple, American Express, and Dairy Queen, investors wonder what becomes of an empire built on patience.

For everyone else, the better question is: how did a man so devoted to boredom make it the most profitable strategy in capitalism?

The Boy Who Counted Bottles

Buffett was born in 1930 during the Great Depression, in a modest Omaha household where thrift was both necessity and virtue.

His father, Howard Buffett, was a stockbroker-turned-congressman; his mother, Leila, a fierce economizer who sometimes skipped meals to save money.

At six, Buffett sold gum and Coca-Cola door-to-door.

By eleven, he bought his first stock — three shares of Cities Service Preferred at $38 each.

When it dropped to $27, he panicked and sold at $40. It soon rebounded to $200.

That early sting became his first principle:

As a teenager, Buffett ran what he later called the most efficient newspaper route in Omaha.

He memorized every doorstep and shortcut, earning more than some of his teachers. When he filed his first tax return, he deducted his bicycle as a “work expense.” ³

Buffett wasn’t popular or polished.

He was fascinated by numbers, probability, and patterns — things that stayed still while everything else shifted.

While classmates dreamed of adventure, he dreamed of predictability: a world that made sense on paper even when people didn’t.

What looked like timidity became foresight.

Finding His Gospel

At nineteen, Buffett discovered The Intelligent Investor by Benjamin Graham.

Graham, his future professor at Columbia, taught that markets swing between fear and greed and that the wise investor buys what others ignore.

Buffett joined Graham’s firm and learned to read balance sheets the way others read novels.

Yet something about his mentor’s style felt cold. Graham saw stocks as equations; Buffett saw them as stories.

He wanted companies with character — brands that endured because people loved them.

The $200 Billion Mistake That Made a Fortune

In 1962, Buffett began buying shares of a dying textile firm called Berkshire Hathaway.

When management tried to underpay him in a buyback, he retaliated by taking control so he could fire them.

It was, he later admitted, a terrible decision. The mills lost money for years, draining cash he could have invested elsewhere.

He estimates that holding on cost him roughly $200 billion in foregone gains. ⁴

But failure became foundation. When he finally shuttered the mills, he repurposed Berkshire as a holding company for other businesses.

Out of stubbornness, he built an empire.

The Empire of Everyday Things

From that shell grew a collection of ordinary businesses: GEICO, See’s Candies, Benjamin Moore, Dairy Queen, American Express, Coca-Cola.

Each reflected Buffett’s preference for the tangible.

He favored “wonderful companies at fair prices” over “fair companies at wonderful prices.”

His genius was not invention but endurance.

Later came Apple, a surprising late-life investment that became Berkshire’s single most profitable holding.

The Gospel of Boring

Buffett still lives in the same five-bedroom house he bought in 1958 for $31,500.

He owns no smartphone and has never sent an email.

His diet? McDonald’s breakfasts and Cherry Coke.

He spends up to 80 percent of his day reading.

I just sit in my office and think,” he says. “That’s rare in business.”

Every year, he writes a shareholder letter - part confession, part comedy, part sermon.

These letters, studied by investors and MBA students worldwide, are admired for their clarity and candor.

When the Oracle Was Wrong

Buffett’s humility was forged in failure.

He avoided tech through the 1990s, missing Amazon, Google, and Microsoft. He stayed loyal to Wells Fargo through scandal.

He once paid $400 million in Berkshire stock for Dexter Shoe, which collapsed; those shares would later have been worth billions. ⁵

He called such errors “tuition payments.” “We learn more from the errors than the triumphs,” he said.

The “Oracle” was never a prophet — just a man willing to be wrong in public until time proved him right.

The Discipline of Stillness

Buffett compares the market to baseball without called strikes. “You can watch pitches forever,” he says. “The pitcher never walks you.”

When panic spreads, he buys. When greed surges, he stops. “Be fearful when others are greedy, and greedy when others are fearful.”

The Buffett Premium and the Next Chapter

Berkshire Hathaway is now worth close to a trillion dollars.

Analysts talk about the “Buffett premium” — the extra confidence investors assign to the company simply because he runs it.

As he transfers daily control to Greg Abel, his longtime deputy, questions remain about whether that premium will survive.

Abel is competent and steady, but charisma cannot be inherited.

The Moral Capitalist

Buffett’s view of wealth has always been paradoxical.

He believes in capitalism, not excess.

He has pledged to give away 99 percent of his fortune, largely through the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, founded by the Microsoft creator and his then-wife to fight poverty and disease.

He co-founded the Giving Pledge, urging billionaires to commit most of their wealth to charity. He has long argued that “the rich should not pay less than their secretaries.”

He credits his late wife, Susie, for shaping his conscience.

Their home was filled with artists and activists — a counterpoint to his spreadsheets.

“She taught me how to live,” he said. After her death, he began giving billions in her name.

The Long Game

Buffett likes to say the best investment you can make is in yourself. He built his fortune not by chasing novelty but by trusting time. He turned patience into a superpower.

Asked once how he wished to be remembered, Buffett replied, “He was a teacher.”

And perhaps that is his final, quiet truth.

For nearly a century, Warren Buffett has shown that greatness in business is not about brilliance or bravado but the courage to stay ordinary.

In a world addicted to speed, he built an empire by waiting.

Sources:

- Entrepreneur, “Warren Buffett’s Wealth Grew More After Turning 65” (2024).

- Buffett, Warren E., and Lawrence A. Cunningham. The Essays of Warren Buffett: Lessons for Corporate America, 5th ed. (Wiley, 2023).

- Schroeder, Alice. The Snowball: Warren Buffett and the Business of Life (Bantam, 2008).

- Berkshire Hathaway Inc. Annual Reports and Buffett’s 2010 letter to shareholders.

- Buffett, Warren E. 1999 Berkshire Hathaway Shareholder Letter.